A Lesson From COVID-19: A History of Racism and Disease in ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi

As someone of Chinese descent who lives in the multicultural mixing pot that is ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi, I find myself thinking about the fact that May is Asian and Pacific Islander (API) Heritage Month, and how the opportunity to reflect on API heritage in the United States could not have come at a better time. In some ways, whatās happening today with COVID-19 is history repeating itself. As the disease has spread, there has also been a rise in anti-Asian sentiment and xenophobic attacks on Asian people throughout the country. These attacks are provoked and encouraged by the dangerous and inaccurate rhetoric spewed by the current administration, such as referring to COVID-19 as āthe Chinese flu.āĀ

Disease outbreaks have long been racialized throughout history and used to systemically scapegoat certain groups of people. This panic-fueled racism intersects with other systems of oppression, such as incarceration, white supremacy, colonization, and poverty.Ģż

Although the anti-Asian sentiment on the mainland has been more extreme, weāre still experiencing traces of it here in , the state that boasts the largest percentage of Asian and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander populations thanks to a unique history of plantation labor immigration from Asia and Western colonization. In fact, ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āiās history of discrimination against API people is one we can learn from.Ģż

When the first were confirmed in early March, Honoluluās Chinatown saw an immediate . The once bustling streets were suddenly silent and empty, while the malls continued to draw in large crowds. Around this time, a friend confided in me about how she feared for the security of her momās job as a waitress in a Chinese restaurant in Honolulu. The restaurant was losing customers, and her mom was losing shifts.Ģż

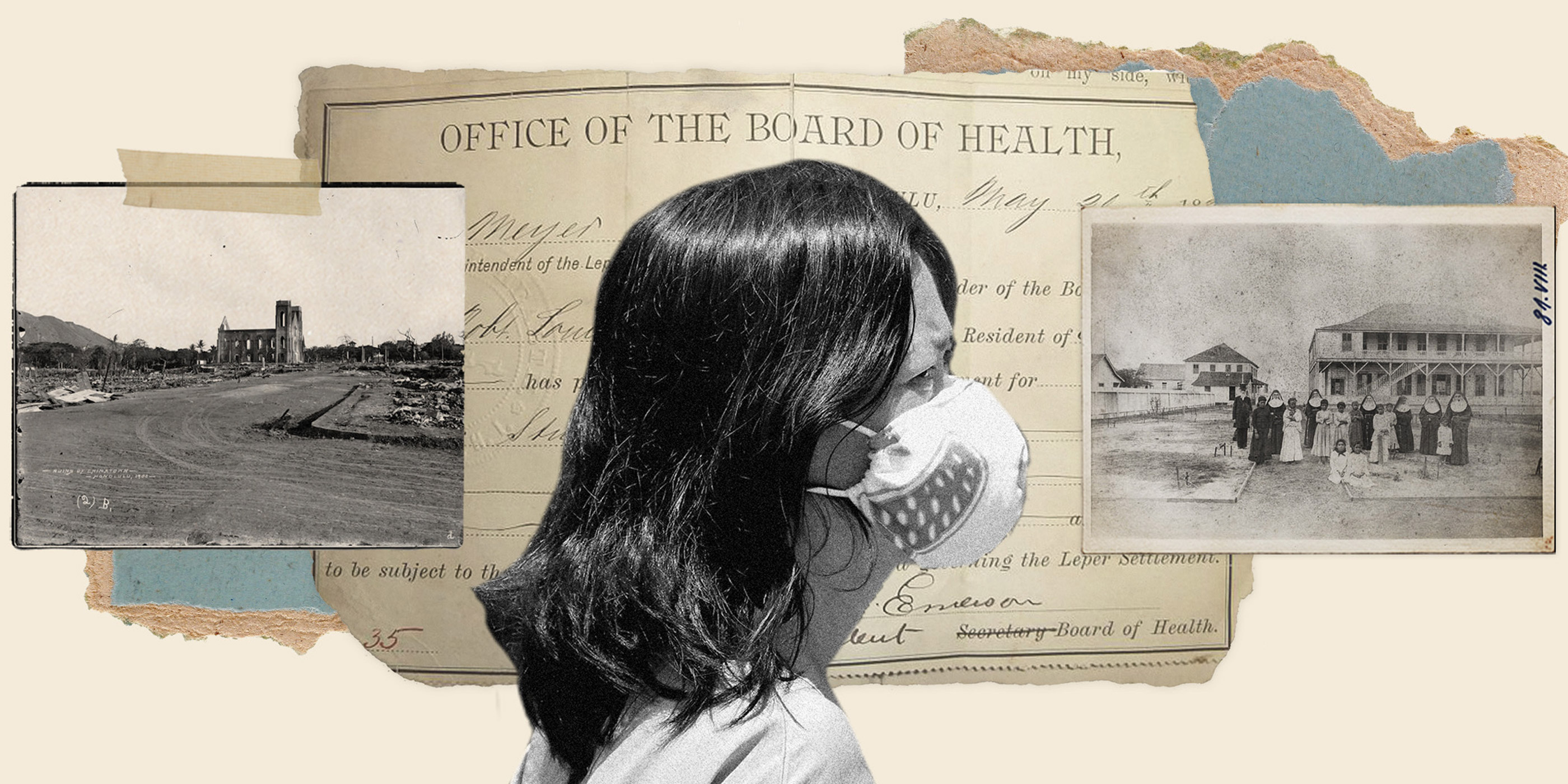

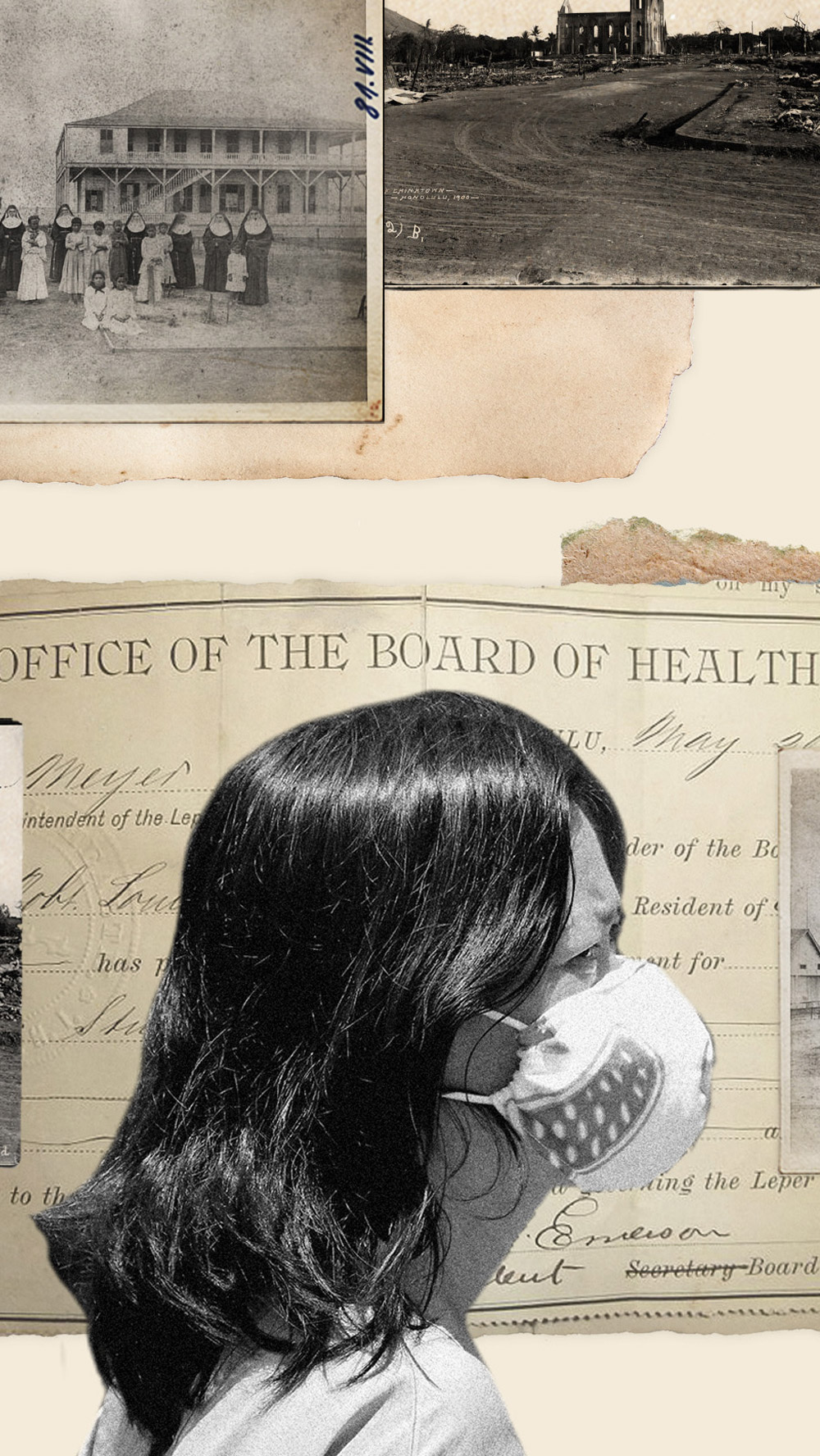

This isnāt the first time Honoluluās Chinatown has experienced racism catalyzed by a public health crisis.The , believed to have originated in China, spread throughout the world and touched down on the islands at the end of the 19th century. During this time, ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi was a thriving economic hub in the Pacific Rim coming to terms with full colonial control and the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. Eurocentric ideology was at a high, which helped foster blatantly racist and false ideas, such as the belief that the āplague seldom attacks clean white people,ā as one Honolulu resident .Ģż

Under economic pressure, officials first sought to quarantine Chinatown, a working class neighborhood made up of shanties and considered ādirty,ā before resorting to burning down entire buildings where plague victims died as a method of āsanitation.ā In early 1900, one of these fires burned out of control and swallowed a fifth of Honoluluās buildings in flames. The residents of the homes that burned down were mainly Chinese, Japanese, and Hawaiian, who were then forced into quarantine camps for weeks with no proper compensation plan to help rebuild their lives.Ģż

This displacement of lower working class families, which would leave them struggling to catch up economically for years to come, was a result of public officials overlooking one of the most vulnerable and therefore least influential populations. This political inaction was illustrative of how a society entrenched in white supremacy and colonialism failed to protect the people not considered valuable ā in this case, poorer people and people of color.

When considering the intersection of racism and infectious diseases in ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi, we canāt overlook the leprosarium on the secluded peninsula on Molokaāi, an island west of Maui. The highly stigmatized , or Hansenās disease, was first diagnosed in the islands in 1848. Little was known about the disease, and it was believed to be more contagious than it actually is. But as with the bubonic plague in Honoluluās Chinatown, racism infiltrated the way it was handled by public health officials.Ģż

From 1866 to 1969, over 8,000 people were permanently exiled to Molokaāi for having leprosy. Those exiled were not only expected to die there, but society also shunned them as āimpureā criminals simply for having the disease. Ķųŗģ±¬ĮĻ 97 percent of those exiled to the settlement were Native Hawaiian, a population already shrinking from other diseases introduced by European settlers, while foreigners with leprosy were reportedly allowed to leave the country. Although those exiled to the settlement were eventually given the freedom to return back to society, many found it difficult to be fully welcomed back, instead choosing to live out their lives on Molokaāi. Today, recall what happened on Molokaāi to be an example of white colonist interest using public health discourse to segregate, tear apart, and ultimately disempower Native Hawaiian communities.Ģż

These examples are not isolated events, and they should not be forgotten. If we donāt learn from the past, we risk further harming groups of people who are already marginalized. In ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi, two populations especially vulnerable to the pandemic ā the houseless and the incarcerated ā are disproportionately made up of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander peoples. Although Native Hawaiians make up 24 percent of the stateās population, they account for 39 percent of the prison population.Ģż

This disproportionate representation shows up in our houseless population as well. In 2019, ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi ranked as the state with the second-highest , and the majority of people who use are Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander. Itās notoriously hard to make ends meet in ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi, where the cost of living is high, but the cycle of poverty is especially difficult for Native Hawaiians, who have been trying to recover ever since Europeans arrived. In 2017, the for all ±į²¹·É²¹¾±āi residents was 9.5 percent, but for Native Hawaiians, it jumped to 13.4 percent ā the disparity likely due to lower education levels and lower wages.Ģż

In California, despite making up a small part of the stateās population, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have the of any group. And these arenāt the only groups of people being affected at a disproportionate rate ā Indigenous, Latinx, and Black communities are also suffering due to racial disparities in our health care system across the nation.Ģż

If this month serves any purpose, it is for everyone ā not just those of API descent ā to reflect on how racism itself is intertwined with systems of oppression. If the numbers above indicate anything, itās that the harmful effects of colonialism and decades of systemic oppression are long lasting and impact countless aspects of many peopleās lives. As a vehicle for racism, COVID-19 presents a critical lesson. This pandemic ā and the others from Hawaiiās history ā sheds light on the damaging legacy of racism and oppression. As health and safety are rightfully on peopleās minds, itās going to take everyone working together to forgo harmful, unproductive racist ideologies and instead advocate for our politicians and institutions to ensure that everyone feels protected and safe ā now, and after the moment of crisis has passed.